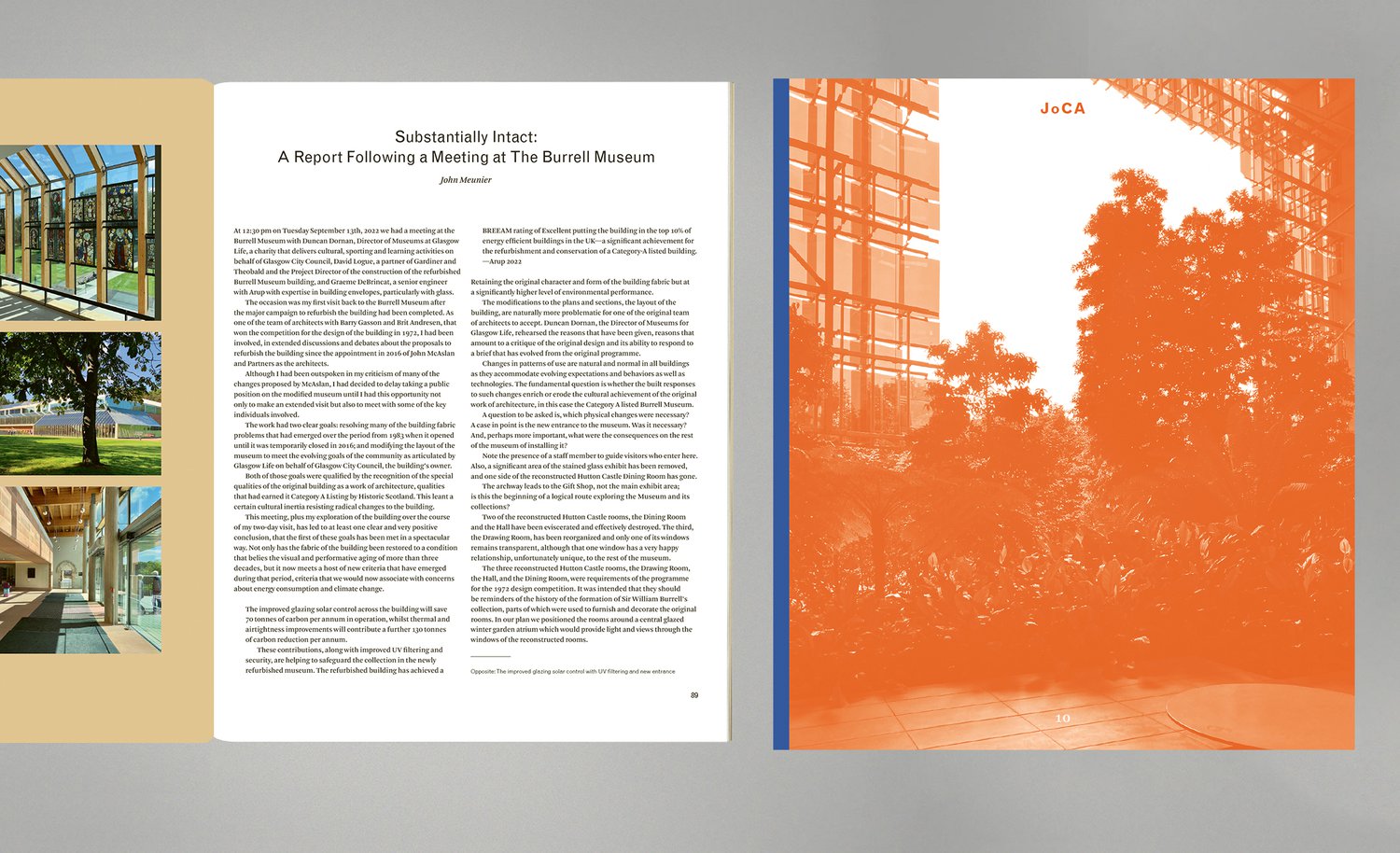

I also met Brit Andresen, one of the architects of The Burrell Collection - alongside Barry Gasson RIP, and John Meunier. Brit contributed to Migrations from Memory. John Meunier appeared in JoCA 2 (and co-authored On Intricacy with me in 2020), and writes here about his reaction to recent changes to The Burrell. Brit suggested, I’m told, that I ‘found my tribe in Brisbane.‘ Why? Well, I think that it is pretty obvious that questions of climatic architecture lie at the heart and soul of Australian architecture. Simultaneously, the primacy of architectural atmosphere has evolved into a poetics of air and acoustics, evolving not out of a bluntly superficial technical sensibility, but from an attitude attuned towards the entangled physical and imaginative character of place and of dwelling. This aerodynamic and poetic architectural attitude is embodied in the timber Queenslander houses that line the hillsides, and hang suspended above river valley. These houses are infused with a richly complex spatial character, one that the supremely talented Brisbane poet David Malouf, who I also met last year (at the launch of The New Queensland House by Cameron Bruhn and Katelin Butler), describes in his essay “The First Place: A Mapping of a World” (1985). Brit gives this essay to her architecture students at The University of Queensland, to be read as a primer in Brisbane spatial qualities and effects. The character of the Brisbane imagination, Malouf argues, is infused with weather, topography, animals, etc., and so human ecology and the resulting architectural urbanity, “offers a different notion of what the land might be”, he suggests. “You learn in such houses”, Malouf observes, “to listen. You build up a map of the house in sound, that allows you to know exactly where everyone is and to predict approaches. You also learn what not to hear… Wooden houses in Brisbane are open. That is, they often have no doors… you can see right through it to trees or sky… verandahs, mostly with crossed openwork below and lattice or rolled venetians above; an intermerdiary space between the house proper, which is itself only half closed-in, and the world outside - garden, street, weather.” In a nutshell – or rather in a Mangrove seed perhaps – I found an architectural culture full of life and refreshingly open, in every sense.”

Patrick Lynch